Earlier this week the BBC reported the drop in file sharing following the court-ordered block of the Pirate Bay (TPB) was short-lived (link to article). The BBC said it had been shown data by an unnamed major UK ISP which confirmed that P2P activity on the ISP’s network had returned to just below normal one week after the block was put in place. Should we all be surprised by this? Of course not. Stopping Internet users in the UK from accessing TPB won’t stop them file sharing. What will stop them file sharing is if ISPs blocked access to all file sharing services. Interestingly enough, most ISPs’ customer-use policies make it clear that the Internet service provided should not be used to infringe copyright. In fact, the usage policy usually forms part of a contract, and therefore any breach of this contract should result in the customer’s account being terminated. Such a scenario never happens. Continue reading “Is the BBC report on the effectiveness of the Pirate Bay block missing the point?”

Earlier this week the BBC reported the drop in file sharing following the court-ordered block of the Pirate Bay (TPB) was short-lived (link to article). The BBC said it had been shown data by an unnamed major UK ISP which confirmed that P2P activity on the ISP’s network had returned to just below normal one week after the block was put in place. Should we all be surprised by this? Of course not. Stopping Internet users in the UK from accessing TPB won’t stop them file sharing. What will stop them file sharing is if ISPs blocked access to all file sharing services. Interestingly enough, most ISPs’ customer-use policies make it clear that the Internet service provided should not be used to infringe copyright. In fact, the usage policy usually forms part of a contract, and therefore any breach of this contract should result in the customer’s account being terminated. Such a scenario never happens. Continue reading “Is the BBC report on the effectiveness of the Pirate Bay block missing the point?”

Tag: isp

Music streaming partnerships a €1.1 billion opportunity for European operators in 2011

A research project carried out by Informa Telecoms & Media, publisher of Music & Copyright, and the streaming music service Spotify has concluded that large mobile operators could add millions of euros to their bottom line by partnering with a music streaming service.

Rapid smartphone uptake combined with the recent rise of streaming services like Spotify have for the first time enabled music to make a substantial impact on operator’s market share, ARPU and churn. By partnering exclusively with an existing player rather than building their own service, fast-moving operators can realise these gains quickly while shutting out competitors.

The study is based on real data from the Swedish telecoms operator Telia and Spotify, as well as research from Informa Telecoms & Media and other service providers and operators. Using this data, the study estimates that an operator in Western Europe with 20 million customers could generate revenues of €77.7 million in 2011 alone from partnering with a streaming service. If the leading player in each Western European market did so, they would collectively generate €1.1 billion in 2011, the study found.

One of the authors of the study, Giles Cottle, said that the research shows how a large Western European operator could “generate millions of euros of revenue a year by partnering with a third-party music service – significantly more than they would gain from offering their own service. Add in other benefits, such as network efficiency, brand awareness and increased lifetime customer value, and the potential for such a partnership becomes very clear.”

Adrian Blair, Director of European Business Development at Spotify, added “music download stores which operators launched prolifically over the last 5 years are commodities and had little impact on core business metrics. Streaming services, by contrast, have proved an effective way to differentiate from the competition and win new customers. They have also been used to upsell high-ARPU devices and reduce churn. Over half of Spotify/Telia customers said they were more likely to stick with Telia as a result of the Spotify partnership.”

The study says that Telia’s experience has helped illustrate best practice to other operators wishing to emulate their success. Churn reductions and potential gains in market share and ARPU resulting from mobile music streaming will not materialize without a clear strategy and focused execution. A high-quality streaming product and the right offer (for both operator and consumer) needs to be combined with effective marketing, a motivated sales force and deep billing integration. Simply offering a popular free service, with little thought put into the way the offer is packaged and marketed, will not yield the kind of results the operator will be hoping for. Yet if they get it right, the rewards are potentially lucrative.

The joint research paper is available on October 20th exclusively through the Informa Telecoms & Media Analyst Community Group on LinkedIn (www.informatm.com/linkedin).

Music & Copyright is a fortnightly research service published by Informa Telecoms & Media.

A global online-music pricing update

There is little correlation between the level of development of an online music market and the number and type of services available. For example, Hungary, which has a weak online music market, has only a few services, but two of them are subscription services, which are considered a newer business model. The number of services in a country also reveals little about the maturity or value of a market. Brazil has over 20 music services but is still a small online music market.

The three most developed online music markets – those in the UK, the US and Japan – all look very different regarding the availability of services. In Japan, over 90% of music services are a la carte, with few subscription services. In the US, two-thirds of services are a la carte and one-third are subscription. Many of the subscription services launched in 2009, but some, such as Rhapsody and Pandora, have been established for several years. The UK has the most diverse music market of the three, with a la carte, ad-funded streaming, bundled and subscription services available. However, the majority of all services are still a la carte.

There is no clear development path whereby as a market matures new services of one type are launched. This is probably because of the national differences in royalties and the strategies of the four major music labels, which do not have a blanket digital policy. Europe is likely to see some homogeneity in the near future as the European Union attempts to make it easier for providers to get Pan-European licenses.

A la carte services dominate

Globally, a la carte is the dominant business model for music services. For Japan and Belgium, over 90% of music services are a la carte. The countries with the lowest proportion of a la carte services are Spain, Poland and Hungary. Single tracks cost close to US$0.99 for most services. In several European countries, this is the lowest price that can be paid for a single track. In the UK, where several new entrants are large companies from other industries, some tracks cost only US$0.46.

South Korea and Russia are the countries in which single track cost the least: between US$0.11 and US$0.52 in South Korea and between US$0.28 and US$0.79 in Russia.

Album prices range between just over US$6 in Russia and more than US$30 in the Netherlands. The most common low price for albums is between US$7 and US$8. There is no single price point for which the majority of albums can be bought for globally.

No homogenous price for subscription services

Subscription services are the second-most-popular service type in many countries. France has the largest number of subscription services relative to total available services, while the US has the largest number of subscription services overall.

In contrast to Japan, where a la carte is the prevalent business model, over half of South Korean online music services are subscription-based. These services offer prices between US$2.18 for 40 songs to just under US$27 for unlimited downloading.

With the publicity that has surrounded it, it is often assumed that Spotify has set the de facto price for music-subscription services, at €9.99 (US$13.50). And although it might be true that some new entrants have copied that price, there is still a real divergence in pricing across this market segment (see fig. 4). Cost of a subscription to streaming services in the US varies from US$3 for ad-free use of Grooveshark and US$5 for unlimited streaming from Napster to US$15 for MOG’s premium service, which includes streaming to the mobile phone.

In the countries where it is available, eMusic’s premium service, US$29.79 in Europe and US$24.99 in the US, is the most expensive. In countries where both are present, eMusic’s €11.99-a-month basic package is more expensive than Spotify’s Premium service.

Bundles and ad-funded streaming yet to make an impact

With services including TDC Play and Touchdiva, Denmark has the highest percentage of bundled music services in countries tracked. With only two services, it is far from being the dominant business model, and few are likely to want to compete with the established TDC service.

Despite TDC Play’s success, bundling a music service with a broadband service is something only a few other operators have done. Part of the reason for this is music labels’ reluctance to allow operators in larger markets to provide a similar service. In the UK, Virgin announced it would offer an unlimited service, but it has failed to bring the service to market a year after the announcement. Telefonica is among the few other incumbents to offer a music service that is bundled with its broadband service, though it also offers the service to nonsubscribers.

Nokia’s Comes With Music service is the only bundled service from a mobile phone vendor. Despite the service’s mixed success, Nokia continues to introduce it in new countries. Other handset vendors are unlikely to follow, but some PC vendors, through partnerships, are launching similar services in 2010.

In the countries tracked, there are only seven pure ad-funded streaming services. Weakened ad spending and the inclusion by established providers are the two key factors. Spain and France have the highest prevalence of ad-funded-only streaming services. But one of Spain’s largest players, Yes.fm, had to close its service because it found that ad revenues could not cover royalty payments. It has since re-launched as an ad-funded service with a subscription tier available.

Music & Copyright is a fortnightly research service published by Informa Telecoms & Media.

Are existing laws, existing education and existing understanding of consumer behaviour insufficient to deal with ‘piracy’?

Recently a UK Government advisory body – the Strategic Advisory Board for Intellectual Property (SABIP) – has bucked the trend by calling for an urgent investigation into consumers’ attitudes and behaviour in relation to offline copyright infringement. It says that too much focus has been placed on looking into online peer-to-peer file-sharing. SABIP is concerned that physical copying by swapping hard drives and memory sticks has been overlooked and may pose a greater threat of piracy than online copying. Although SABIP believes that there is a lot of offline copying taking place in this way, it says that further research is needed to establish the extent of it. Initial SABIP research (conducted by BOP Consulting) shows that consumers are more interested in price, quality and availability of material than whether it is legal or illegal. The natural implication seems to be that if legal material happens to be better quality than unlawful copies, that will influence consumers to buy legally. That is food for thought, particularly in light of the following survey of legal purchasers – who break the law.

73% of 2000 people surveyed by Consumer Focus in the UK admitted to being confused by what they were legally permitted to copy or record. Most of the consumers did not know that it was illegal to copy something that they have legitimately paid for (such as a CD) over onto another medium (such as a computer) for their own personal use. Consumer Focus accused the current copyright laws of being outdated and not reflecting what consumers reasonably believe to be the case when using music just for themselves to listen to. Indeed, it seems clear that many people who are not illegal peer-to-peer file-sharers are still clearly breaking the UK’s copyright laws, despite not realising it. The congruence between the law and what people believe to be the law seems to be in a bit of a mess.

Turning to online protection, in the UK, initial steps to enforce the law seem to have failed. The first prosecution in the UK of a person charged with illegal peer-to-peer file-sharing ended with a not guilty verdict. A man ran an unauthorised music-sharing web site called Oink from his home in the North East. The site allowed members to share files. From its launch in 2004 until police closed it down in 2007, over 20 million music files were shared. Users had to make a donation to the site so that they could invite friends to become members too. The site operator made a considerable amount of money – some £10,000 a month, in donations. However, the site operator was found not guilty of the offence of conspiracy to defraud by Teesside Crown Court.

In Australia, a court ruled that an Internet Service Provider (ISP) was not liable for the unauthorised peer-to-peer file-sharing habits of users to whom that ISP merely provided access. Roadshow Films claimed that iiNet (an ISP) had authorised copyright infringement by its users, but the Australian Federal Court disagreed. The judge said that the fact that copyright infringement was occurring on a wide scale across the ISP’s network did not mean that the ISP had authorised the wrong-doing as it was not compelled to stop the infringements. Mere knowledge that infringement was taking place was not enough. As with English law, Australian copyright law forbids the doing or authorisation of the doing of anything which infringes someone else’s copyright. The two legal systems have common roots, and the decision may therefore be persuasive (although not binding) on similar English court cases.

Over the past few months, the UK government has turned to a different approach with its Digital Economy Bill. When passed, the Digital Economy Bill will see file-sharers being identified, warned and ultimately stopped from having full Internet access. There is some recent uncertainty whether the Government has shifted its position in the Digital Economy Bill and adopted a more lenient line in respect of illegal peer-to-peer file-sharers. Instead of cutting off persistent file-sharers from the Internet, the Government now says that their accounts will be temporarily suspended – although it is unclear what this means. It is not clear if this is a change or not. According to Jim Killock, of the Open Rights Group – a body against the proposed legislation – nothing has really changed. He says that temporary account suspension still means that families will be stopped from using the Internet.

As to cost – the Government has announced that rights-holders will have to pay 75% of the cost of dealing with Internet pirates under the proposed Digital Economy Bill and ISPs will be required to foot the balance of 25% of the cost – although the entertainment industry had hoped for a 50/50 split.

However, the law may say (or be about to say) one thing but the technical ability to identify file-sharers is far from fool-proof. Indeed it would seem to be a pre-requisite to any enforcement under the Digital Economy Bill that file-sharers are identifiable. Recently, Virgin Media announced that it is planning to trial new software called CView which will analyse file-sharing by its customers. However, Privacy International – a privacy rights watchdog – has taken issue with the ISP’s actions and has asked the European Commission to report on the legality of the proposed software use. Privacy International claims that the trial would breach the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act, under which it is a criminal offence to intercept communications without consent unless certain exemptions apply. However, Virgin Media counters that it is not actually identifying individual users. Instead, it is conducting the trial to see how much of the traffic through its service is illegal file-sharing. It wants to find out what it can do to reduce illegal file-sharing and the trial will give it useful information to help to achieve that. Virgin Media has admitted that it would be possible technically to use the deep packet inspection software to identify Internet protocol addresses (from which individual users could be identified) but has announced that this is not currently its plan.

Importantly, Virgin Media claims that CView will not help with the proposed Digital Economy Bill precisely because it says that CView does not actually identify anyone.

It seems that the ability to identify file-sharers as file-sharers beyond a reasonable doubt (the criminal standard of proof) or even on a balance of probabilities (the civil standard of proof) remains in doubt at present. That must surely put the utility of the proposed Digital Economy Bill in doubt too.

Ways to deal with file-sharing seem to be in state of flux. It is not just files that are being shared – the problem is being shared as well – between those responsible for the legal aspects, the technical aspects and the educational aspects of this modern problem. And, of course, by those losing money as a result.

This blog entry was written by Mark Weston, who is a partner at Matthew Arnold and Baldwin LLP. There he heads the Commercial/IP/IT team. He joined in 2004 after many years in the Magic Circle law firms. Although Mark’s team deals with non-contentious and contentious matters, Mark’s own practice has primarily evolved focus on non-contentious matters in all areas of commercial law, information technology law, intellectual property law and Internet and on-line commerce law.

Music & Copyright is a fortnightly research service published by Informa Telecoms & Media.

Could blanket licensing for ISPs be the solution to file sharing?

In most developed music markets around the world, associations representing rights holders, music companies and performers are engaged in negotiations and discussions with governments to develop guidelines, and in some cases legislation, to control the level of file sharing across P2P networks. Almost without exception, ISPs have come out against such measures. Whether ISPs have benefitted from illegal file sharing through higher subscription numbers is perhaps an argument for another day. But are ISPs missing an opportunity to cash in on file sharing and at the same time be the solution to a problem they have helped exacerbate?

Several ISPs already offer bundled music services as an extra option on top of their regular subscription price and have reported significant interest. There is also evidence to suggest that bundled services could become popular with consumers. Last year, research from Entertainment Media Research/Wiggin for the 2009 Digital Entertainment Survey revealed that regular downloaders of unauthorized music said they would be willing to pay for legal content if it were bundled with the price of their ISP connection. The problem is, all of these bundled services have concentrated on trying to entice P2P users away from file sharing. Advocates of monetizing file sharing point to the fact that the system has been largely created by consumers, which in the process have formed the largest-ever repository of music. Since music is already a shared medium, why would so much effort be concentrated on changing consumer behavior, particularly since consumers have already given a clear indication of what they want?

Providing a blanket license to an ISP that legitimizes the behavior of file sharers comes with an almost innumerable list of considerations. How payments to rights holders and music companies would be determined and the fairness of imposing a fee for all ISP subscribers regardless of music use are just two of the most obvious. But these are not insurmountable. Applying a fee for a service brings with it issues of quality and service guarantees. If a file shared is substandard – a not-uncommon occurrence in the world of P2P – then whose responsibility is it to rectify the problem? On this issue, perhaps, file sharers would most likely accept this in the knowledge that their actions were not deemed illegal and that rights holders were now receiving a payment for their services, in the same way authors and performers do for use of their content through public performance.

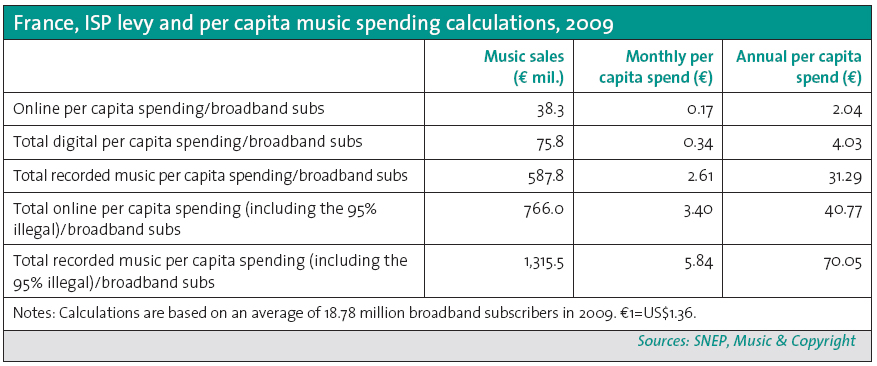

One of the central issues and perhaps the most crucial to the adoption of such a system is price. Establishing a level that is acceptable to Internet subscribers and rights holders is problematic but not impossible. Music & Copyright has crunched several numbers and come up with some simple guidance where the debate surrounding the possible fee level could begin.

Taking France as an example, the trade value of online music sales (excluding streaming) totaled €38.3 million in 2009. That is the equivalent of an average of just over €2 per internet subscriber. To use this figure as a pricing guide is obviously much too simplistic, because it does not take into account physical music purchases or purchases via mobile. It also assumes no shift in music-buying patterns, which would inevitably occur if an ISP fee were added to a broadband subscription. Let’s take the per capita guide to the other extreme, if the total 2009 music-sales figure (online, mobile and physical) were used and all music sales in the year were made via broadband, the per capita trade-value figure for 2009 would be slightly over €31, or €2.60 a month. It’s equally fair to suggest that this guide figure is only slightly less flawed than the previous one, because it does not address the monetization of the considerable amount of music shared via P2P – the whole reason to add a fee in the first place.

Estimating the number of tracks illegally shared online is speculative. At the press launch of the IFPI’s Digital Music Report 2010, published last month, the global trade body estimated that 95% of all downloads are unauthorized. If that figure were accurate for France and the published trade value of online sales were just 5% of possible value, then factoring the 95% into an online-sales-only calculation would put the annual ISP fee at around €40 (€3.40 a month), or €70 (€5.84 a month) if the figure for mobile and physical were included. It should also be noted that these figures are based on trade revenues and do not include author’s/artist royalties or ISP management fees. However, the inclusion of these figures would still result in a surprisingly low figure and one that is comparable with many of the “unlimited” DRM-protected subscription service fees charged by ISPs.

ISPs have resisted any price increases to compensate for file sharing and would most likely see the above as anti-competitive. But if a “P2P monetizing fee” resulted in a reduction in churn, the benefits to an ISP would extend far beyond solving their perceived aiding of file sharing and include the generation of more revenues and lower expenses through greater subscriber retention. Music companies may also have an incentive to pursue such an approach, particularly if the problem of file sharing can be solved without alienating their customers.

Music & Copyright is a fortnightly research service published by Informa Telecoms & Media.

You must be logged in to post a comment.